Blog

A 5a edição do CTM – Festival for Adventurous Music and Art ainda se chamava Club Transmediale. Aconteceu no final de Janeiro de 2004, durante um inverno bem frio e abrangeu 9 dias na famosa boate Maria am Ostbahnhof no centro de Berlim. Esse galpão em uma antiga fábrica abandonada era usado para a fabricação de motores para barcos e está localizada em frente a Ostbahnof (principal estação de trem na extinta Berlim Oriental). É um desses lugares estranhos e vazios em que não havia muito, mesmo até hoje.

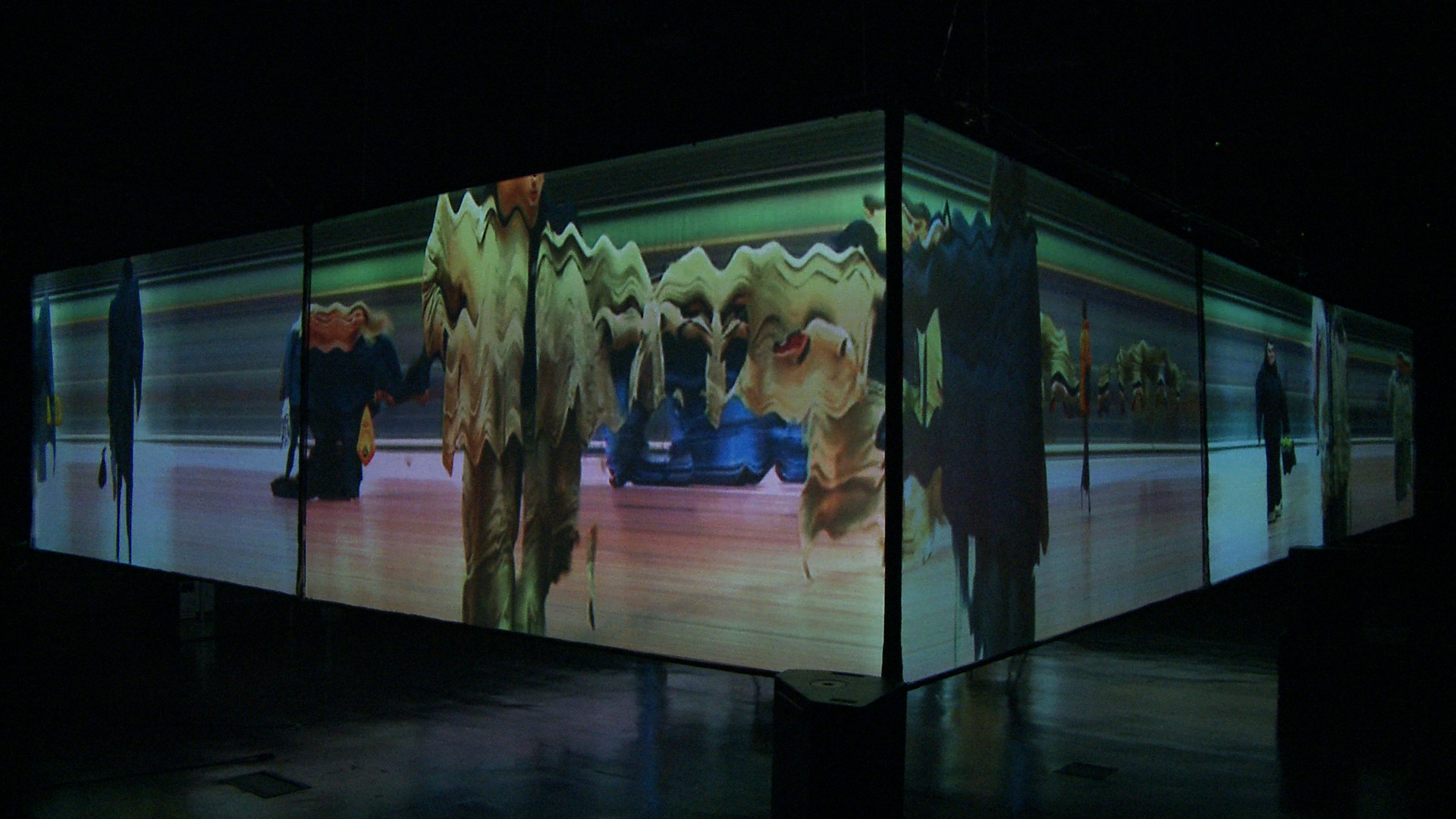

Embora a quinta edição não tenha sido celebrada como um aniversário, nós notamos um aumento dramático em comparecimento; nós esprememos até 1400 visitantes por vez no Maria, um prédio de concreto sem janela. Três ambientes receberam dois palcos com mais de 160 artistas, e 10 instalações de arte particulares feitas especialmente para ou adaptadas para o festival. Foi também o primeiro ano em que oferecemos uma área de bastidores.

O tema da 5a edição foi Voa Utopia! Citando o comunicado à imprensa: “Sonhos e ilusões têm sido abandonados pela nossa sociedade atual apenas na superfície. No entanto, após o colapso das grandes ideologias do século XX, há de novo um aumento na procura por conceitos que apontam além das restrições do factual e que oferecem visões dos velhos e dos novos potenciais da ação criativa.” A nossa sociedade parecia estranhamente presa na rotina. Utopias haviam desaparecido completamente. Nenhuma idéia política e nenhuma invenção tecnológica nos desafiou, o tempo parecia quieto e funcionando (mecanicamente) bem. A crise financeira parecia longe, globalização estava começando a acelerar e CTM olhava para a Europa Oriental e a sua cena de música experimental desconhecida.

O fim da música de computador foi proclamada ao passo que abordagens mais performáticas tomaram conta da cena de música experimental. O corpo representava o último lugar para expressar Utopias. Assim, o CTM 2004, questionava o papel do corpo e do gênero na música eletrônica. Poderosas performances no palco foram apresentadas por artistas como Chicks on Speed, T.Raumschmiere, e Miss Kittin. Quase 40% dos artistas eram mulheres. Essas experiências acabaram em uma antologia de textos publicada com o título “Gendertronics” (ed. Surhkamp).

Por mais que fôssemos bem-sucedidos em atrair o público, em garantir verba, com a reposta da imprensa internacional e também em receber um número crescente de organizadores de festivais internacionais, nós estávamos apenas começando a perceber o quão o nosso empenho era frágil. Nós começamos o festival em 1999 como uma exploração de sons experimentais dentro da cena eletrônica (boates). Na época, as boates de Berlim apresentavam sonoridades mais inquietantes e desafiadoras do que hoje em dia. A boate era uma espécie de espaço utópico em si, promovendo uma bolha atemporal, um buraco negro para uma grande variedade de experiências, intercâmbio e encontros sociais. A boate estava ali para compartilhar conhecimento, para discutir e para se perder em igualdade social. Status não vinha de dinheiro, roupas ou estrelato. Por isso, não víamos a necessidade de uma área de bastidores até a nossa 5a edição.

A nossa jornada começou como um projeto e hoje continua como um projeto. O nosso empenho em receber um financiamento estável, multi-anual público, nunca veio como fruição, e ainda hoje, perto da nossa 17a edição, nós ainda estamos nos baseando nos subsídios de projetos anuais. Muitos produtores culturais estão convictos de que atividades tornam-se entediantes quando se recebe apoio estável por muitos anos. A busca ou caça por financiamento e patrocínio de projeto pode te manter jovem e bonito como festival, mas prejudica todo o trabalho do evento ano a ano. E quanto à sustentabilidade? Como você apóia uma cena próspera quando você não pode oferecer apoio financeiro aos outros, muito menos a você mesmo?

A 5a edição de um festival é frequentemente uma espécie de compasso que aponta para onde festival pode ir e o quanto do seu espírito utópico você pode manter. Olhando para trás, é também a edição na qual você se pergunta se você quer continuar, ou se você deveria acabar por cima e navegar por novos mares. Eu tenho dois conselhos, os quais eu nunca segui, mas que continuam na minha cabeça: nunca faça algo por mais de 9 anos, porque se torna chato, e 10 anos de auto-exploração no campo cultural são o suficiente como contribuição de uma pessoa para a sociedade. Talvez eu tenha decidido adicionar outro ciclo de 9 e 10 anos, tanto que eu vou continuar até a 19a edição me perguntando a mesma questão – “qual é o melhor momento para parar?”

Como uma criança dos anos 80, eu nunca fui treinado para pensar em sustentabilidade, legado ou legitimidade já que o mundo acabaria em breve por causa da 3a Guerra Mundial nuclear. Divirta-se, faça o que quiser e estará tudo bem, aproveite a vida e faça o bem, respeite o próximo e faça do mundo um lugar melhor mesmo que os outros decidam destruir tudo. Esse espírito Voa Utopia! continua sendo um tema oculto de muitas edições dos festivais CTM, no sentido de que nós ainda batalhamos para mostrar que a música tem coisas importantes a dizer, que o seu contexto de criação diz muito sobre mudança social, antecipa o futuro, e dá espaço para pensamento e reavaliação se você realmente estiver escutando.

Finalmente, 2004 foi o ano no qual CTM conscientemente convidou todos os diretores de festivais que estavam presentes no festival para uma sessão de intercâmbio seguindo o exemplo de muitos projetos colaborativos que estavam sendo apresentados então (SHARE, Htmelles-Festival, etc.). Essa reunião, que juntou um contingente notável de diretores de festivais da Europa Oriental, foi um dos primeiros impulsos da futura rede ICAS. Utopias não podem ser realizadas sozinhas, apenas em colaboração próximas com outras. Uma lição também aprendida na 5a edição. Então Voa Utopia!

__

The 5th edition of CTM – Festival for Adventurous Music and Art was still called Club Transmediale. It took place late January 2004, during a very cold winter, and spanned 9 days at the famous Maria am Ostbahnhof club in Berlin’s centre. This old deserted factory shed used to be used for manufacturing motors for boats and is located opposite the Ostbahnof (the former East Berlin main rail station). It’s one of those strange and empty places that did not really change much, even until now.

Even though the fifth edition was not especially celebrated in the anniversary sense, we saw a dramatic increase in attendance; we squeezed up to 1400 visitors at a time into Maria’s windowless concrete building. Three rooms hosted two stages with over 160 artists, and 10 particular art installations made especially for or adapted to the venue. It was also the first year that we offered a backstage area.

The 5th edition topic was Fly Utopia! To quote the press release: ”Dreams and illusions have been abandoned by our present society only on the surface. Rather, after the collapse of the 20th century’s grand ideologies, there is once again an increasing search for concepts that point beyond the restrictions of the factual and that offer visions of the old and the new potentials of creative action.” Our society seemed strangely stuck in a routine. Utopias had completely vanished. No political ideas and no technical inventions challenged us, times seemed quiet and working (mechanically) well. The financial crisis was far away, globalisation was just beginning to accelerate and CTM looked out to Eastern Europe and its undiscovered experimental music scene. The end of laptop music was proclaimed as more performative approaches took over the experimental music scene. The body represented the last place to express Utopias. CTM 2004 thus questioned the role of the body and gender in electronic music. Powerful stage performances were seen by artists such as Chicks on Speed, T.Raumschmiere, or Miss Kittin. Almost 40% of the artists were women. These experiences ended up in an anthology of texts published under the title, “Gendertronics” (ed. Surhkamp).

As much as we were successful in attracting the public, in securing funding, with the international press response and also in hosting an increasing number of international festival organisers, we were only then starting to realise how fragile our endeavour was. We started the festival in 1999 as an exploration of experimental sounds within the electronic (club) scene. At this time Berlin clubs were presenting more disturbing and challenging sounds than nowadays. The club was a sort of utopian space in itself, providing a timeless bubble, a black hole for a great variety of experiences, exchanges and social encounters. The club was there to share knowledge, to discuss and to get lost in social equality. Status didn’t come from money, clothes, or stardom. It’s the reason why we did not see the need for a backstage until our 5th edition.

Our journey started as a project and today we still remain a project. Our endeavour to receive a stable, multi-annual public funding has never come to fruition, and so today, on the threshold to our 17th edition, we are still based on yearly project grants. Many cultural workers are convinced that activities become boring when they receive stable, multi-year support. The quest or hunt for project funding and sponsorships may keep you young and beautiful as a festival, but takes it toll on all that work on the event year to year. And what about sustainability? How do you support a thriving scene when you can’t offer adequate financial support to others, never mind yourself?

A festival’s fifth edition is often a kind of a compass that points to where your festival could go and to how much utopian spirit you can keep. Looking back, it is also the edition where you have to ask yourself if you want to continue, or if you should end on a high note and sail to new shores. I have two pieces of advice, which I never really adhered to but that still turn round and round in my head: never do something for more than 9 years because then it becomes boring, and 10 years of self-exploitation in the realm of culture are enough as one person’s contribution to society. Perhaps I decided to add another cycle of 9 and 10 years, such that we will continue into the 19th edition asking ourselves the same question – “when is the best time to stop?”

As a child of the ’80s, I was never trained to think about sustainability, legacy or legitimacy since the world would soon end due to a nuclear WWIII anyway. Enjoy yourself, do what you want and all will be fine, enjoy life and do good, be respectful and make the world a better place even if others decide to destroy everything. This Fly Utopia! spirit has continued to be an underlying theme of many CTM festival editions, in the sense that we still strive to show that music has important things to say, that its context of creation tells a lot about societal change, anticipates the future, and gives place for thought and re-evaluation if you are truly listening.

Finally, 2004 was the year where CTM consciously invited all festival directors that were present at the festival to an exchange session following the example of many collaborative projects that were being presented then (SHARE, Htmelles-Festival, etc.). This meeting, which gathered a notable contingent of Eastern European Festival directors, was one of the first impulses of the future ICAS-network. Utopias cannot be realised all on your own, but only in close co-operation with others. A lesson learned also from the 5th edition. So Fly Utopia!